There is science supporting the environmental principles of regenerative

farming

– keeping living roots to build soil organic matter, enhance water infiltration,

and sequester carbon; fostering biodiversity to create a system that can better

sustain itself in times of adversity; integrating

animals

as walking composters to enhance biology and fertility; etc. But the truth is,

regenerative practices are not going to make a positive dent in the food system

long term unless there is a true economic case for farmers and others in the

value chain. And there is.

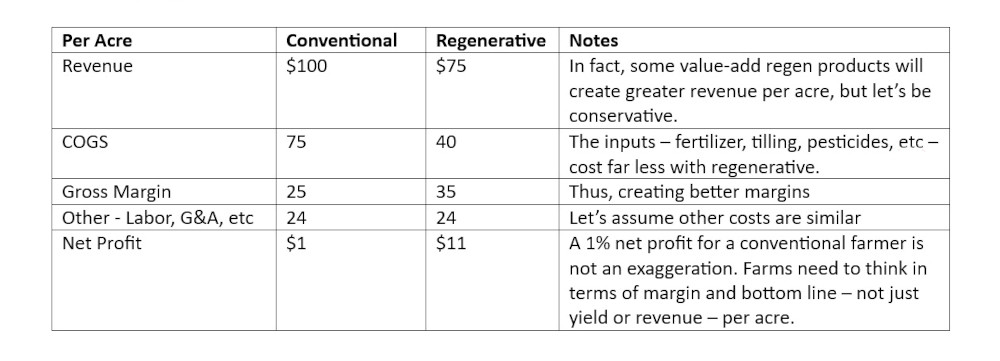

Here's a (very) simplistic example to frame the logic:

This is the lower-cost economic case. There is another side of the economic

case — which involves creating more value-added, higher-margin,

less-commoditized products that will, in fact, yield greater revenues per acre

(and also increase the ‘Other’ costs such as processing, packaging, etc vs just

raw commodity versions of a crop or animal). We’ll talk about the value-added

case down the road.

One challenge many conventional farms face is one-time conversion costs and

investments — i.e. all the infrastructure they’ve built and the way they’ve

managed their farm was built for a conventional business model. This can’t be

ignored. There is significant federal funding and private grants available to

facilitate some of those costs; but regardless, conventional farming today is a

very low (if any)-margin, price-taker business model vs. trying to build a

better-margin, price-maker economic model.

Don’t take my word for it

In addition to the growing number of brands that are

cultivating regenerative supply

chains,

there are real-world case studies that actualize the above logic:

Paul Shoemaker is ED at Carnation Farms — a community-based hub for regenerative food and agriculture that educates and empowers the work of culinary & food and farming professionals.

Published Sep 16, 2024 8am EDT / 5am PDT / 1pm BST / 2pm CEST