Many US and European companies that previously offshored their

industrial operations to cheaper countries such as China are now relocating

manufacturing back to their home countries.

This phenomenon, known as

nearshoring

or

reshoring,

has taken off massively since 2020 — first, due to COVID-19; but also because of

rising geopolitical friction with China, the global manufacturing hub. A

Kearney study shows that 96 percent of US

CEOs

intend to bring back their manufacturing to the US, or have already taken steps

to do so — up from 78 percent in 2022.

However, simply moving a factory from China or Taiwan to Arizona or

Ohio is not sufficient for US brands to meet the demands and values of US

consumers. In a November 2023

survey by

American Compass and YouGov, 42 percent of US consumers feel that

“manufacturing is important to a healthy, growing, innovative economy” and

clamor for US-made products.

The bad news is that 62 percent prefer to pay higher prices to support US

manufacturing, rather than pay more to combat climate change (38 percent); over

half of US adults surveyed prefer policymakers to focus on enhancing the US

industrial sector, rather than improving the environment.

The survey reveals three competing desires — revitalize left-behind communities,

boost domestic manufacturing, and combat climate change — which respondents find

it challenging to juggle and harmonize.

What if Western firms capitalized on the reshoring trend in the US and Europe to

completely transform manufacturing value chains in order to address their

customers’ three competing aspirations? Brands can achieve that Holy Grail of

balancing economic growth, social cohesion, and environmental stewardship if

they boldly reinvent their outmoded value chains.

Limitations of global value chains

In today's customer-centric, collaborative and rapidly changing economy, the

traditional value chain —

a set of interconnected activities to develop and bring a product to customers —

faces four major limitations.

The linear value chain fails to engage creative 'prosumers'

Brands view customers as nothing more than walking wallets. They see buyers as

passive receivers of the value chain's output — excluding them from actively

participating in R&D, production and marketing. However, empowered by the

internet, social media, digital tools such as 3D printing, creative spaces such

as FabLabs, and decentralized energy

systems,

passive buyers are evolving into active

“prosumers” — spearheading the

Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Maker

movement.

Futurist Alfin Toffler predicted

that this “prosumation” movement will accelerate during the 21st century and

blur the line between production and consumption, compelling businesses to

reconsider their engagement with customers throughout the value chain.

The insular value chain doesn’t favor B2B collaboration

The conventional value chain focuses internally. It outlines a series of

connected activities carried out by a company using exclusively its own

resources — and those of its suppliers and partners — to turn an idea into a

final product or service for the customer. From this perspective, a brand’s

competitive advantage lies in its capability to optimize its own value

chain more

efficiently than rivals.

In the interdependent business environment, however, the concept of competitive

advantage is being replaced by cooperative advantage. Innovative firms strive

to collaborate with other companies, even competitors, to jointly create new and

larger “blue ocean” market

opportunities that are

advantageous for all. Thanks to B2B sharing

platforms,

companies in different sectors can today combine their R&D, manufacturing and

go-to-market resources to co-create greater value for all stakeholders.

The static value chain doesn’t deliver agility and resilience

Using lean manufacturing techniques such as Six

Sigma

and

Kaizen,

businesses have fine-tuned their value chain to achieve efficiency gains. Today,

brands leverage their “lean” value chains to produce and deliver their products

cheaper and quicker. But these well-oiled, static value chains lack the agility

and

resilience

needed to respond to unforeseen market shifts.

Similarly, when cataclysmic events such as pandemics, wars and natural disasters strike,

many businesses find it

challenging

to swiftly adjust their inflexible value chain processes to prevent

disruptions.

In a VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) world, businesses must

collaborate with suppliers and partners to create agile and resilient value

chains

that can respond quickly to supply and demand fluctuations.

The wasteful and complex value chain is unsustainable

From apparel and automotive to food and energy, every industry value chain —

whether globally dispersed or nationally integrated — is notoriously wasteful

and unsustainable. For instance, from the cotton field to the shop, a pair of

jeans travels 1.5 times around the

planet

— which adds up to 65,000 km and the associated emissions. In the US, fresh

produce travels 1,500

miles from farm

to plate. Around 5 percent of the

electricity

generated in the US is lost in transmission and distribution, which is

sufficient to power all seven Central American countries.

The complexity of industry value chains makes them wasteful and unsustainable.

University of Illinois researchers studied 9.5 million food transit

routes in the

US. One food journey follows “corn grown on an Illinois farm to a grain silo

in Iowa, from where it is transported to feed cows in Kansas. After

processing, the meat products then make their way back to Illinois and onto the

shelves of a grocery store in Chicago.”

Likewise, to produce a single passenger car — which is made up of 20,000

parts

— a carmaker must orchestrate a multi-tiered, global value chain of roughly

8,000 suppliers. Sadly, only 13 percent of

companies

have full visibility into their multi-tiered value chain. The more layers in a

value chain, the greater its Scope 3

emissions

(especially upstream

ones)

— which account for up to 90

percent of

many businesses’ total carbon footprint.

Bottom line: firms must stop orchestrating hyper-global value chains that are

inflexible, closed, and unsustainable. Instead, they must build and facilitate

hyperlocal value networks that are adaptable and sustainable, and maximize

social impact.

The rise of hyperlocal value(s) networks

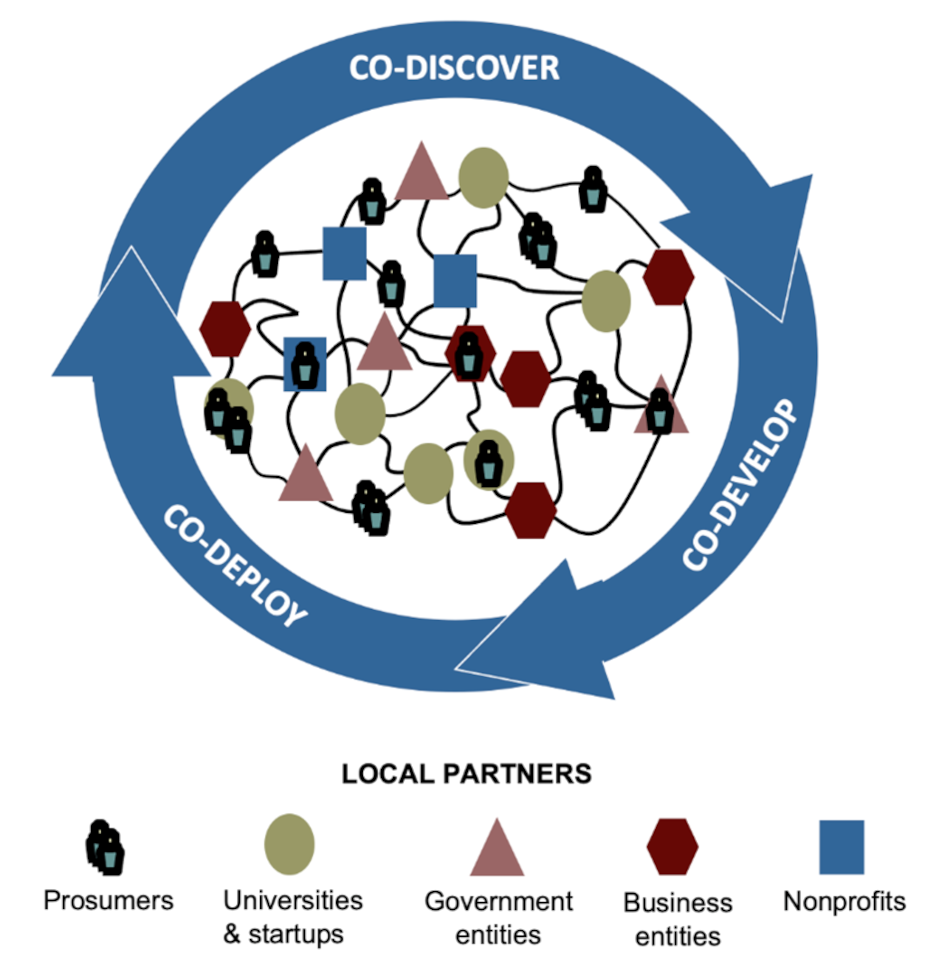

A hyperlocal value network (HYLOVAN) is a dynamic, open ecosystem that

proactively involves a diverse set of stakeholders within a specific area — such

as a city or county — to collaboratively develop customized solutions that

address local market and social requirements.

Each word in HYLOVAN highlights unique features that make the system way more

impactful than a traditional value chain:

“Hyperlocal” refers to the fact that a HYLOVAN can have a geographical

range that could be as limited as a neighborhood or as extensive as an entire

city — in the US, it does not extend beyond the county level.

In order to cut supply chain expenses and environmental footprint, a HYLOVAN

primarily obtains its inputs — from raw materials to workforce — from nearby

sources. A large portion of what it produces — such as products and services —

is consumed within the local area, although some can be delivered to nearby

communities using eco-friendly transportation methods. As a result, a HYLOVAN is

intrinsically frugal.

Take Vertical Harvest’s vertical farm in Jackson Hole,

Wyoming: It is three

stories tall and only takes up 1/10 of an acre, yet it is able to grow and

deliver 100,000 pounds of fresh leafy greens year-round to local restaurants and

groceries. On average, Vertical Harvest’s healthy produce only travels 6 miles

from the farm to the consumer — a much shorter distance than fresh food’s

typical 1,500-mile journey in the US.

Vertical Harvest minimizes its carbon footprint but maximizes its social

handprint: 40 percent of its staff are individuals with

disabilities.

The organization is expanding its successful hyperlocal food production model

to the state of Maine, where its hydroponic greenhouse will grow annually

over 2 million pounds of fresh

produce

and employ around 50 underserved community members.

Similarly, in early 2023, CarbonCure and

Heirloom — two startups focused on carbon

removal and utilization, conducted a successful pilot

project

where they captured CO2 from the air and stored it permanently in concrete for

use in local construction projects. The whole value chain — the carbon-capture

unit, the concrete batch plant and construction sites — was situated end to end

within the San Francisco Bay Area.

“Value(s)” means a HYLOVAN aims to valorize — unleash the full value of —

physical, natural, intellectual, cultural and social assets that have been

underused or devalued in a local area due to economic or historical factors.

Moreover, a HYLOVAN promotes positive values — such as equity, trust,

sustainability — within a community by embodying them.

For instance, the French postal service La Poste

teamed up with SUEZ — a leading provider of circular

environmental services — to set up Recygo, a joint venture to collect and

recycle office waste. Today, 75,000 postal workers and SUEZ employees collect

65 tons of office waste each

day at over 23,000 sites across France. Recygo recycles the waste and creates

socio-economic value locally. The waste is first sorted at a local center that

employs economically disadvantaged people and then recycled at one of the 84

regional paper mills

situated throughout France.

“Network” refers to the resilient and flexible properties of a HYLOVAN,

which — in contrast with a monolithic, linear value chain — can continuously

adapt and

evolve

to effectively react to shifts in its surroundings. A HYLOVAN can accelerate

innovation, minimize risks and capitalize on new opportunities swiftly by openly

sharing information with all members — facilitating fast and efficient

coordination.

A hyperlocal value network engages diverse local stakeholders | Image credit: Navi Radjou

A hyperlocal value network engages diverse local stakeholders | Image credit: Navi Radjou

GRDF — France’s top natural gas distributor — has

established a network of Living

Labs

rooted deeply within French territoires (a geographical unit similar to US

counties), with the goal of repositioning local citizens as the focal point of

the energy transition. Conceptualized by MIT scholars, a Living

Lab is an open innovation ecosystem

that draws together diverse community members — residents, entrepreneurs,

companies, non-profits, government entities — to jointly create valuable goods

and services that benefit and improve the public welfare.

In each community, GRDF’s Living Lab applies agile development processes to

engage local partners to iteratively test, learn and deploy disruptive solutions

— such as the development of green gas and agroecology. These solutions are

tailored to maximize sustainable value in the local context but can be

replicated in other places. For example, by generating biomethane

locally using organic

waste from agriculture and food, and then injecting it into GRDF’s distribution

network, communities achieve energy self-sufficiency, lower emissions, enhance

soil health, protect water resources and generate employment opportunities.

As of today, 547 methanization

units

are injecting directly into GRDF’s distribution network. By deploying these

Living Labs across France, GRDF is proactively scaling out its own operating

model

to enable and lead the decentralized production of renewable

gases

— which in turn, will speed up the decarbonatization of local communities. GRDF

projects that by 2050, 73 percent of the gas flowing in France’s distribution

grid could be green gas — most of which can be produced

locally.

US and European brands that want to reshore manufacturing and reindustrialize

their countries need to first revamp their entire value chains. By building and

facilitating hyperlocal value networks that are open, adaptable and deeply

rooted in communities, businesses can gain agility and resilience and maximize

sustainable local impact.

Read more about the frugal economy:

This article has been partially adapted from the author’s upcoming book, The

Frugal Economy: A Guide to Building a Better World with

Less

(2024), published by Wiley and Thinkers50.

Get the latest insights, trends, and innovations to help position yourself at the forefront of sustainable business leadership—delivered straight to your inbox.

Navi Radjou is a French-American scholar and advisor on innovation and leadership.

Published Sep 26, 2024 2pm EDT / 11am PDT / 7pm BST / 8pm CEST