Wakame seaweed — a familiar ingredient in Japanese cuisine — is a harmful

aquatic plant that proliferates rapidly at beaches and fishing ports around the

world; it has been named one of the world’s 100 worst invasive

species

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

(IUCN).

Traditionally, few cultures outside of Japan, Korea and China

consume wakame. Yet the many benefits of seaweed are starting to be recognized —

as the basis for sustainable alternatives to fossil fuel-based products

including

plastic,

animal

feed

and

fuel;

and as part of a growing focus on marine plants for mineral-rich

nutrition in the face of a

deepening global food crisis caused in part by climate change.

Here, we introduce Uzushio Shokuhin, YK — a wakame producer on a quest to show the world the nutritional and culinary benefits of wakame, and

to unlock the broader potential of this destructive yet delicious seaweed.

From Japan to France, and back again

Image credit: wirestock_creators

Image credit: wirestock_creators

One region where wakame has exploded as an invasive species is Brittany,

France. Around 50 years ago, all of Brittany’s oysters were nearly wiped out

by an infectious disease. Juvenile shellfish were imported from Japan, but they

brought along wakame spores, and the seaweed soon became an aquatic nuisance.

Then, a local company, Algolesko, decided to

turn that problem plant into a nutrient-rich source. Algolesko began farming

high-quality wakame in the rich waters of the Bay of Biscay, a designated

nature preserve; yet it had issues with the processing technology required to

ship the fresh seaweed.

Uzushio Shokuhin president Hiroki Goto recalled his first visit to the

Brittany seaweed farms as part of his research to discover opportunities for

exporting wakame overseas.

“As soon as they pulled wakame out of the water at the Algolesko farm, I

thought, ‘What is this!’ Incredibly high-quality wakame just kept coming and

coming,” he says. “For about 30 years, I had been hearing about wakame in

France, but I had no idea it was of that level. It was remarkable. Then, I was

also surprised to find that they were storing this high-quality wakame just by

salting it — that method hadn’t been used in Japan for over 50 years. And to be

honest, it doesn’t produce delicious wakame. I thought it was an enormous waste.

It made me realize that we’d never get more people to eat it, and that exports

wouldn’t succeed, until we first showed people how delicious it is.”

In 2022, Uzushio Shokuhin and Algolesko entered into a technical support

agreement that enabled the Brittany region to produce seaweed that is both

delicious and retains its vibrant color. Thanks in part to this, wakame and kelp

produced in Brittany are now ingredients that are hailed by French chefs, too.

The next step in promoting wakame as a food, Goto said, is developing new

recipes and preparation methods for it. Even in Japan, wakame tends to be used

in limited ways — such as in miso soups, salads and pickled dishes. Goto hopes

that introducing it into an unfamiliar culinary culture could give rise to

completely new recipes and ways of eating it, and that “reverse-importing” those

newfound possibilities back into Japan could also boost its domestic consumption

and help revitalize the wakame industry.

Nutritional benefits for people, animals and oceans alike

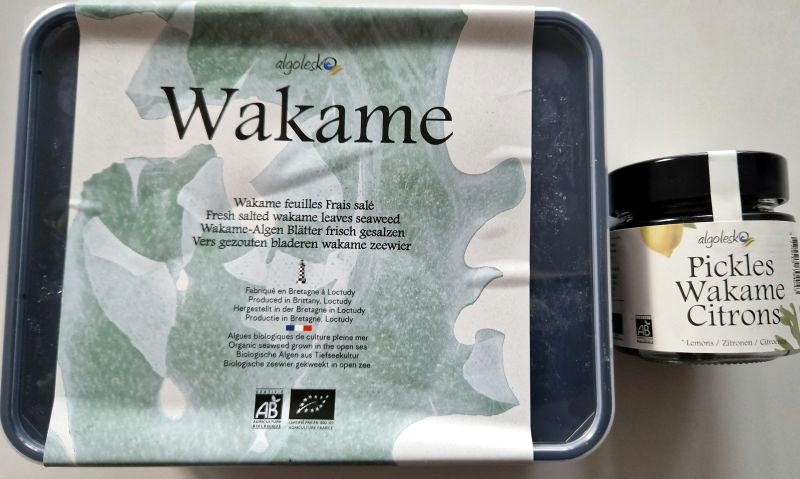

Algolesko's Wakame Pickles won a grand prize at the 2024 Seafood Excellence Global Awards | Image credit: Algolesko

Algolesko's Wakame Pickles won a grand prize at the 2024 Seafood Excellence Global Awards | Image credit: Algolesko

Uzushio Shokuhin is also pursuing the potential in non-food uses for wakame in

order to make the industry more sustainable.

Thanks to environmental protection measures, water quality in Japan’s Seto

Inland Sea has improved after being

heavily polluted in the 1960s and ‘70s. Yet while the waters have become

clearer, there has been a decline in nitrate — one of the ocean’s three

primary

nutrients

— a deficiency that makes it difficult for phytoplankton to

grow,

which reduces the ocean’s ability to store

carbon.

One way to address this problem is to regenerate soil through land-based

livestock and agriculture farming, and create a mechanism for soil nutrients to

flow out into the sea.

For this process, Uzushio Shokuhin developed animal feed made by fermenting

wakame holdfasts — the root-like part of the plant. Feeding this to pigs has

been proven to improve feed efficiency and reduce susceptibility to disease.

What’s more, the manure from these pigs becomes high-quality, organic fertilizer

that can be sprinkled on fields to nurture crops and improve soil fertility. The

nutrients from this fertile soil are then directed into the sea, helping to

boost marine ecosystem biodiversity — including the growth of wakame and other

seaweeds.

“When it comes to using livestock and agriculture to benefit the fisheries

industry, Europe is more advanced. Speaking to farmers in France, I was

really impressed by their level of awareness and broad vision,” Goto said. “I

want us to also engage in this new challenge, taking a cue from all the

different initiatives in Japan and around the world, so that this land continues

to provide food even 100 years in the future.”

Whether it’s helping improve global food security or contributing to a

regenerative value chain for primary-sector industries, the sustainability

potential of wakame continues to proliferate.

Get the latest insights, trends, and innovations to help position yourself at the forefront of sustainable business leadership—delivered straight to your inbox.

SUSCOM

Published Jul 9, 2025 8am EDT / 5am PDT / 1pm BST / 2pm CEST